I previously did a research post on an Indigenous history of Banff National Park and I got curious to also learn more about the history of the city of Calgary, the Bow River valley beyond the Rocky Mountains and the surrounding prairies in Southern Alberta.

If you are wondering where the name Calgary originates, it is named after Calgary Bay in Scotland. The Scottish name is derived from the Gaelic words Cala-ghearridh meaning pasture by the bay.

The initial fort was built in 1875 at the meeting of the Bow and Elbow Rivers, which was called Fort Brisebois. The next year 1876, it was changed to Fort Calgary. Calgary dropped the name “Fort” from its name when it was incorporated as a city in 1884.

As for an indigenous name for Calgary, the name Mohkinstsis (MOH-kin-stiss) is an anglicization of the traditional Blackfoot name for the area where the Bow River and Elbow Rivers meet.

But as you will see each local First Nations group has a different name in their own language for the Calgary area but interestingly, each one seems to have a similar meaning.

A First Nations History of Calgary And Southern Alberta:

Southern Alberta has been inhabited for at least 12,000 years, according to the latest archeological evidence.

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Blackfoot were known as the “People of the Buffalo” as hunting buffalo provided their key source of food, shelter and clothing. They put virtually every part of the buffalo to use. The meat was cooked over a fire, the bones were turned into tools and the thick buffalo hides were used as clothing and covering for their tipis.

They were a warrior culture skilled in the art of warfare who frequently clashed with their neighbouring tribes. Today, you can learn about the ancient cultural traditions of the Blackfoot at key archeological sites such as the ancient petroglyphs and pictographs at Writing On Stone Provincial Park and their most significant buffalo jump where they herded buffalo off a series of cliffs called the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump World Heritage Site.

The first European settlement was founded in Northern Alberta at Fort Chipewyan on the MacKenzie River in 1788 but it would be another hundreds years before mass colonial settlement took off. Initially, the European fur trade and the introduction of new technology brought by Europeans lead to increased prosperity for First Nations in Alberta.

The introduction of the horse and the rifle made it much easier for First Nations hunters to hunt and kill the buffalo. By the end of the 19th century, the Blackfoot had become wealthy from a lucrative trade in buffalo meat, fur and artifacts but soon overhunting and the slaughter of the buffalo by colonial settlers and farmers looking to protect their crops would reduce the buffalo herds to near extinction.

By the late 19th century, a combination of famine, war and disease — mainly smallpox, measles and influenza that came from European livestock and for which First Nations had no immunity reduced their populations by over 50% and forced tribes groups like the Blackfoot and others to negotiate treaties with emerging colonial government.

Treaty 7 Lands

On December 4th, 1877 Treaty 7 was signed between the Crown of England and the Blackfoot Chief Crowfoot at Blackfoot Crossing along the Bow River 75 km east of Calgary. The treaty was signed by 5 First Nations groups: the Siksika (Blackfoot), Kainai (Blood), Piikani (Peigan), Stoney Nakoda (Iyârhe) and the Tsuut’ina (Sarcee).

The treaty established native land reserves and promised annual payments and provisions to the First Nations tribes as well as the promise of continued hunting and trapping rights on the land that was surrendered to the Crown. Most of the promises of Treaty 7 never materialized.

As part of the treaty, the Canadian government promised to help the First Nations tribes transition to an agricultural lifestyle but they were given poor quality land where it was difficult to grow crops. In the coming decades, residential schools were set up to teach indigenous children how to read and write in English to participate in the modern economy but their impact was largely to break the oral storytelling and language lineages of the First Nations tribes.

The residential schools punished students for practicing traditional customs, language and religion and instead sought to assimilate them into the British culture and Christian religion. While the schools almost succeeded in eradicating First Nations languages, fortunately there is still a community of several thousand Blackfoot speakers and a new generation of Blackfoot is reconnecting and revitalizing their traditional customs and culture by learning their oral language and stories.

Here’s the best video I can find about the early history of Alberta.

Here are more details about each of the major First Nations people with historical ties to the area and their history in Calgary and the surrounding region.

1. Niitsitapi or Blackfoot

The Siksika, a Blackfoot tribe called the place that is present-day Calgary “moh-kíns-tsis,” meaning “elbow.” According to records from 1875, they expanded the name to “moh-kíns-tsis-aká-piyoyis,” which means “elbow many houses.”

Calgary is the traditional territory of the Blackfoot Confederacy but when Europeans set up trading posts for the fur trade, several other First Nations groups migrated to the area.

The origin of the name Blackfoot is a bit of a mystery. Some people say they got the name because they dyed their moccasins black. Other says it comes from their association with the Buffalo as the hooves of the buffalo are black.

Blackfeet spirituality is based on the animistic belief “in a sacred force that permeates all things, represented symbolically by the sun whose light sustains all things”. They hold Pow Wow celebrations throughout Southern Alberta in the summer and they are known for their Sun Dance Celebrations, a sacred ritual of renewal and cleansing for the tribe and the Earth.

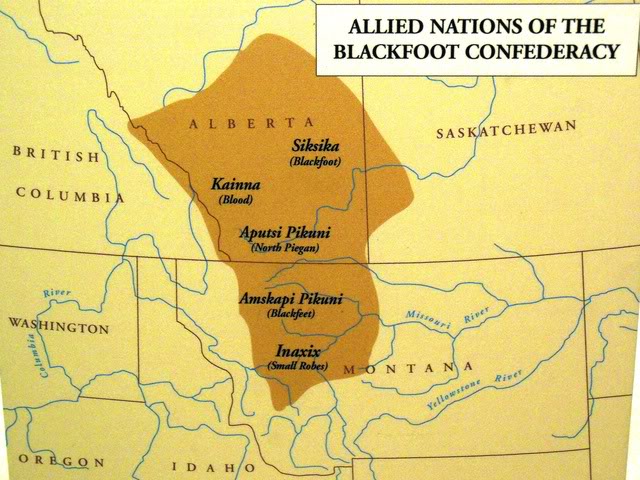

Traditionally the Blackfoot were nomads who roamed Southern Alberta from the North Saskatchewan River that flows through Edmonton to as far south as Yellowstone River in Montana. Here’s a map of traditional Blackfoot territory:

There are three branches of the Blackfoot peoples in Alberta, who call themselves “Niitsitapi” (pronounced nee-itsee-tah-peh) meaning “the Real People.” They are made up of the following three bands in Alberta who share a common language, each with a distinct dialect:

• Siksiká Nation (pronounced Six-ih-gah) also known as the Blackfoot.

• Kainai Nation (pronounced Gaa-nah) also known as the Bloods or Káínawa.

• Piikani Nation (pronounced Be-gun-nee) also known as Aapátohsipikáni or Northern Piikáni.

There is also a large Blackfoot tribe living in Montana called the Piegan Blackfeet (Ampskapi Piikani) that are closely related to the Northern Piikáni.

The two key areas of the Blackfoot culture in the wider Calgary area are the confluence of the Elbow and Bow Rivers near where Calgary’s downtown sits and Blackfoot Crossing about 100 km further down the river, which were the two main fords for crossing the lower Bow River that became important gathering points to exchange goods and celebrate festivities.

Today, the largest reserve in Canada is the Kainai Nation lands, which is 1,342.9 km² between the city of Lethbridge and Pincher Creek in Southern Alberta. The Siksiká Nation has the second largest reserve in Canada about 100 km east of Calgary just off the Trans-Canada Highway 1.

You can learn about the history and culture of the Siksiká people at the excellent Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park, which was the site of the 1877 Treaty No. 7 signing on the hills above the Bow River.

A Blackfoot woman named Heather Black (O’takii Tsowakii) leads guided hikes and workshops in Southern Alberta and the Canadian Rockies through Buffalo Stone Woman that provide a local First Nations perspective.

This documentary from the Shining Mountains series follows mountain guide, pilot and cinematographer Guy Clarkson on an ecological journey through the Rockies and talks about the sacred hunting grounds of the Blackfoot nations in the Rockies.

2. The Tsuut’ina

The Tsuut’ina named the area where the rivers meet in Calgary “kootsisáw” which means “elbow.”

The Tsuut’ina Nation (pronounced Sue-tin-ah) means “many people” or “beaver people”. They were formerly called the Sarsi or Sarcee, derived from a Blackfoot word meaning “stubborn ones” who they were in constant conflict with over territory. Because of its origin from a rival First Nations group, the term is now viewed as offensive by most of the Tsuutʼina.

The Tsuutʼina language is an Athabaskan language that is closely related to the languages of the Dene groups of northern Canada and Alaska, and also to those of the Navajo and Apache peoples of the American Southwest. This is in contrast to the geographically nearer Blackfoot language and the Cree language, which are Algonquian languages spoken across Canada and the United States.

They operate the Tsuut’ina Culture/Museum and Grey Eagle Resort & Casino on their reserve lands that border the southwestern city limits of Calgary and stretch west to eastern Bragg Creek, Kananaskis and the Moose Mountain area.

This short film explores the culture, traditions and history of the Tsuutʼina Nation and their long rivalry with the Blackfoot Nations.

3. Stoney Nakoda

The Stoney Nakoda called the Calgary area “wincheesh-pah,” which translates as Elbow as well.

The Stoney Nakoda (pronounced Stow-nee Nah-koh-duh) are also known in their own language as the Iyârhe (ee-YAH-hhay) which means “Peoples of the Mountains”. They came to be known as the Stoney by Europeans because of their use of heated stones to cook their meals.

Traditionally, the Stoney Nakoda roamed the lands along the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains stretching from the edge of today’s Glacier National Park in Montana to the North Saskatchewan River and west to the Continental Divide.

The Stoney Nakoda comprise the following 5 bands:

• Bighorn

• Bearspaw

• Chiniki

• Wesley

• Eden Valley

Just off the Trans-Canada Highway 1 (Exit 131) outside of the small town of Mînî Thnî (also known as Morley) as you are approaching the Rocky Mountains is the Chiniki Cultural Centre, which is an excellent place to learn about the history and culture of the Stoney Nakoda people (it’s inside the Smitty’s restaurant).

There are also some good cultural and historical displays at the Stoney Nakoda Resort & Casino, which you will pass by just before you enter the mountains at Mount Yamnuska, which provides the backdrop for the resort.

They speak a northern dialect of the Dakota language, a division of the Siouan language group that is spoken across the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America.

The best educational video I could find is about the Assiniboine People (Stone Sioux or Nakoda People) who in the 1800s were members of the “Iron Confederacy”, with the Cree People.

4. The Cree

In the Cree language, the Calgary area is known as otôskwanihk meaning “at the elbow” or otôskwunee meaning “elbow”.

The Cree are the largest group of indigenous people in Canada today. In Alberta, the Cree are divided into two main groups, the Plains Cree or Paskwāwiyiniwak who migrated to live on the prairies in the early 1700s, and the Woodland Cree or Sakāwithiniwak who live in the boreal or northern forest region.

In Alberta, the Woodland Cree territories are made up of four reserves in northern Alberta (Cadotte Lake, Simon Lake, Golden Lake, and Marten Lake). Cree peoples are spread widely across Canada.

5. Métis Nation

The Métis people are a post-contact Indigenous nation, born from the unions of European fur traders and First Nations women in the 18th century.

The Métis people are a post-contact Indigenous nation, born from the unions of European fur traders and First Nations women in the 18th century.

Alberta is home to more than 127,000 Métis people and is the only province in Canada with a recognized Métis land base. There are 8 Métis Settlements in Alberta, comprising 5121 km².

This short video explains the origins, diversity and controversies surrounding Métis people in Canada.

Where To Learn More About First Nations Culture:

If you want to learn more about First Nations in the Treaty 7 lands and the history of Canada from an indigenous First Nations perspective here are some resources to explore:

1. Download the IndigiTRAILS app for your iPhone or Android smartphone. It provides audio-driven walking tours of popular Calgary geographical landmarks from an indigenous perspective, including Prince’s Island Park, Nose Hill Park, Inglewood Bird Sanctuary, Pearce Estate Park and Fort Calgary.

2. Experience A Pow Wow during the summers, which are First Nations festivals of celebration, sharing, dance, music and pride.

3. Support local First Nations nonprofits like Soul of Miistaki, which was founded by a Blackfoot woman named Cassie Ayoungman with the intention of offering diverse people an inclusive experience of the outdoors.

4. Another local nonprofit Spirit North helps transforms the lives of Indigenous youth by inviting them to build their leadership skills and discover their strengths through sport and play.

5. The Multicultural Trail Network is a nonprofit that provides inclusive outdoor adventure programs for BIPOC youth and new refugees to Canada living in Calgary to experience the mountains.

6. Support the Aboriginal Friendship Centre of Calgary and The Impact Society, which support local First Nations people living in the city of Calgary through social, cultural, education and health initiatives.

7. Native Land is a resource to learn more about Indigenous territories, languages, lands, and ways of life.

8. The University of Alberta offers an excellent 12-lesson online course about Indigenous Canada on Coursera.

59. I’m a big fan of watching documentary films to go deeper into interesting topics so here are 15 excellent documentaries to watch about First Nations and Native American History.

10. Educate yourself about the 94 Calls To Action for Truth and Reconciliation.

I hope you found this post educational and that it sparks your curiosity to learn more about the First Nations people in Western Canada.

- 10 Sustainable Travel Trends Driving The Future of Tourism - March 9, 2025

- 10 Tips To Sell Out Your Transformational Retreats In 2025 - February 20, 2025

- Build 10 Habits That Free Up Your Time With Mindful Coaching - February 11, 2025