You are probably familiar with the land acknowledgement for the city of Vancouver. There are different variations but generally, it goes something like this:

“I acknowledge that I am on the traditional unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples who have been stewards of this land since time immemorial.”

While this land acknowledgment is an important step toward reconciliation, most people living in Vancouver know very little about the history, culture and traditions of these First Nations. I hope this guide can help illuminate their stories and spark your curiosity to learn more from local First Nations peoples.

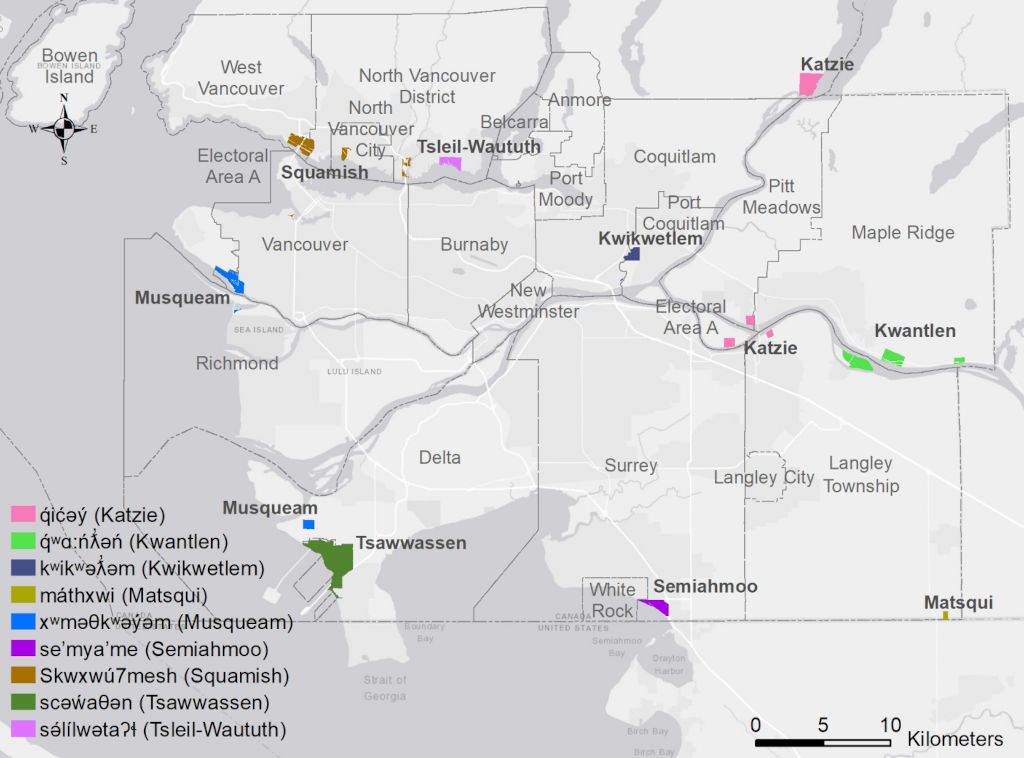

The Metro Vancouver area is on the traditional unceded territories of 10 local First Nations:

1. Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm)

2. Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh)

3. Tsleil-Waututh (sə́lílwətaʔɬ)

4. Tsawwassen (sc̓əwaθən məsteyəxʷ)

5. Kwantlen (q́ʷɑ:ńƛ̓əń )

6. Katzie (q́ićəý̓)

7. Kwikwetlem (kʷikʷəƛ̓əm)

8. Matsqui (máthxwi)

9. Qayqayt (qiqéyt)

10. Semiahmoo (se’mya’me)

Here are the areas where these First Nations tribes live today in the Lower Mainland:

In this article, I’m mainly going to cover a First Nations history of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations who live in the city of Vancouver and the surrounding Burrard Inlet.

Why British Columbia Is Considered Unceded Territories

Today 95% of the land area of British Columbia is considered unceded territories. In the Kumtuks series, former Vancouver mayor and historian Sam Sullivan tells the story of how British Columbia was established.

The area of British Columbia is unique among the lands of the former British Empire (as far as I know) as it was never legally ceded to the Crown of England through a treaty or other legal agreement.

As a result, the original First Nations inhabitants are in court today fighting for their rights to their traditional lands and to establish legal agreements that codify their relationship with the government of British Columbia.

The origin of the name Vancouver comes from the British Royal Navy captain George Vancouver who led a four-and-a-half-year voyage of exploration and sailed into what’s now called the Burrard Inlet on June 13th, 1792.

The indigenous name for Vancouver is generally accepted as K’emk’emeláy (pronounced “KEM-kem-a-lie), which is based on a seasonal indigenous village where Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh people gathered that was once near the Downtown East Side. The name is derived from a word in the Squamish language that means “the place of many maple trees.”

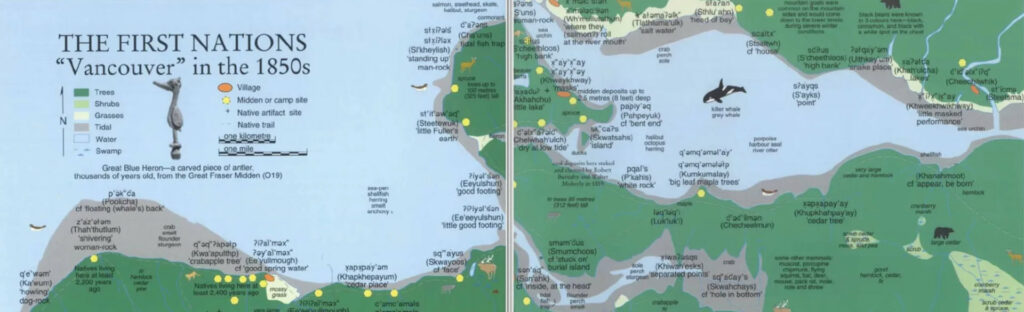

Here’s a First Nations map of the traditional unceded territories and the different language groups of the Pacific Northwest coast:

The History of Stanley Park

There was once a large village in Stanley Park called X̱wáýx̱way (in the Lumberman’s Arch area), which was home to a mix of Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh people.

What is now called Stanley Park was made a military reservation in 1859 and the native inhabitants living in X̱wáýx̱way and a smaller nearby village called Senakw, were relocated to nearby reserves.

In the 1880s, surveyors and road builders completely demolished the long houses that remained in the X̱wáýx̱way to create the Park Drive perimeter road.

There has never been a proper archeological survey done of Stanley Park but there are likely hundreds of archeological sites around the park as it was a pivotal area for fishing and trading along the Burrard Inlet.

Coast Salish Language, Culture And Traditions

The languages spoken on the British Columbia coast are grouped today under the Coast Salish language family, which is similar to other language family groups such as the Germanic language family, which includes English, German and Dutch languages.

A language group doesn’t mean the different cultures get along but they do share some language ties. The term Coast Salish derives more from anthropology than community self-description. Most indigenous First Nations people on the coast refer to themselves as members of a specific tribe and don’t like to use terms given by non-Indigenous entities.

First Nations peoples on the British Columbia coast typically lived in longhouses made from the Western Red Cedar tree, which is called the Tree of Life as it along with the abundant salmon provides the foundation of the Pacific Northwest coastal indigenous way of life.

Their longhouses could be as large as 60 metres long and 20 meters wide. They were built with large cedar posts and slabs. Typically, as many as 10-15 families and over 100 people lived in a single longhouse. You can visit a recreated longhouse today at the Museum of Anthropology at UBC.

All parts of the sacred Western Red Cedar tree were used by Coast Salish peoples, providing them with shelter, clothing, weapons, medicines and canoes. Because there is a natural preservative in the wood that slows the decay of the Western Red Cedar logs, they are used for totem poles as well.

Coast Salish Spirituality And The Potlash

The traditional First Nations practice of carving totem poles was originally practiced by a handful of tribes on the Northwest coast but since the early 20th century, many other indigenous people have adopted the practice across North America.

Totem poles typically document important events, commemorate ancestors and define family lineages and kinship groups or clans using animal motifs such as the eagle, raven, thunderbird, bear and salmon. Contrary to the common misconception spread by early missionaries, they were not worshipped.

Indigenous forms of embodied spirituality often referred to under the anthropological term Animism are nearly universal throughout the world among hunter-gatherer cultures. This way of being in a living, breathing world animated by spirit and sentience is often completely misunderstood and mischaracterized by scholars from literate, monotheistic cultures who are the ones largely documenting it in books and research papers.

Colonialism ultimately served to subjugate and suppress animism because it gave hunter-gatherer cultures the experiential knowledge, oral storytelling wisdom lineages and sensory adaptability to live independently of modern civilization.

Interestingly, indigenous First Nations people rarely willingly joined the colonial society while Europeans who joined or were captured by tribal societies often didn’t want to return to the competitive and ruthless world of early colonial times.

Benjamin Franklin observed this phenomenon in 1753, writing, “When an Indian child has been brought up among us, taught our language and habituated to our customs, yet if he goes to see his relations and make one Indian ramble with them, there is no persuading him ever to return.”

An important ritual in many Coast Salish cultures was the Potlash ceremony, which was conducted by wealthy families where they gave their wealth away to the rest of the tribe. The term ‘Potlatch’ has been taken from a Nootka Indian word meaning “gift”.

The Potlash ceremonies were outlawed in 1885 by the colonial government as it was seen as subversive but in 1951 the laws were rescinded. Here’s a documentary film about how important the Potlash was to the First Nations’ way of life on the BC Coast and the struggle to revive this revered tradition.

To better understand the distinct First Nations cultures and traditions of the area, here is a more in-depth history of the three biggest First Nations groups that live in the city of Vancouver:

1. Musqueam Nation (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm)

The name xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) comes from the flowering plant River Grass, known as məθkʷəy̓ in the Musqueam Halkomelem dialect, which once grew so abundantly throughout Musqueam territory that the area became known as the place where məθkʷəy̓ grows.

Today, the Musqueam Nation lives along the northern mouth of the Fraser River bordering the Vancouver neighbourhood of Southlands and the Endowment Lands that make up the University of British Columbia (UBC) and Pacific Spirit Regional Park.

They traditionally had a warrior village at the site of Wreck Beach today, where they would protect their hunting and fishing grounds from other First Nations groups, particularly the Squamish with whom they had a rivalry with.

The Musqueam have been living continuously at their main winter village, Xwméthkwyiem, at the mouth of the Fraser River, for 4,000 years. There is archaeological evidence at areas such as c̓əsnaʔəm (Marpole) that dates back over 4,000 years and at St. Mungo’s and Glenrose Cannery where it dates back to 8,000 to 9,000 years.

There was once a Musqueam village on the Deadman Island side of Stanley Park as well as other villages at Jericho Beach, Prospect Point and Point Atkinson in West Vancouver’s Lighthouse Park.

Want to learn Musqueam names for different sacred places in Vancouver? Visit the interactive Musqueam Place Names Map. You can also visit the Musqueam Cultural Centre, where cultural tours can be pre-booked through their website.

2. Squamish Nation (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh)

The Indigenous language of the Squamish Nation is the Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw) language. It is distinct from but related to the Halkomelem dialects that are spoken by the Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh. Their language is more closely related to their Shishalh neighbours and the Sechelt language (St’át’imcets) that is spoken on the Sunshine Coast.

The Squamish have reservations land in numerous villages in North Vancouver and their traditional territory extends up Howe Sound, through the town of Squamish and to Whistler.

At the time of first European contact, the Squamish people had villages in the areas around present-day Vancouver in places like Stanley Park, Kitsilano and False Creek area, as well as the Burrard Inlet.

A central part of Squamish history in their oral storytelling culture is the stories of supernatural deities often called The Transformers. According to Wikipedia, “these Transformers, were three brothers, sent by the Creator or keke7nex siyam. These three beings had supernatural powers, often using them to “transform” individuals into creatures, stone figures, or other supernatural entities.”

Three prominent Squamish oral legends involving the Transformers involve the Stawamus Chief that looms over the town of Squamish, Siwash Rock in Stanley Park and the Two Sisters that are known today as the Lions.

The best way to learn more about the Squamish culture and traditions is to book a tour with indigenous-run Talaysay Tours in Stanley Park where you’ll learn about local plants that Coast Salish people have harvested for food, medicine and technology for 1000s of years.

I also highly recommend visiting the Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre in Whistler.

3. Tsleil-Waututh Nation (Səlilwətaɬ)

The Tsleil-Waututh Nation call themselves the “People of the Inlet” and they speak a dialect of the Halkomelem language (called hunq’umin’um’ in their dialect). The Halkomelem language is spoken by 41 different First Nations in southwestern British Columbia.

On the eastern Burrard Inlet, the Tsleil-Waututh have their main village called Xwméthkwyiem. Historically, Cates Park (Whey-ah-wichen) in North Vancouver was an ancestral village site. Their place name for this area means “facing both directions” and “facing the wind.”

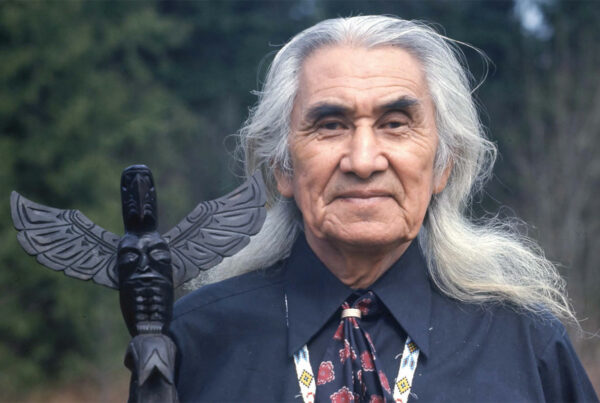

The most famous member of the Tsleil-Waututh was Chief Dan George who was a well-known actor, poet and native rights advocate. I highly recommend the book The Best of Chief Dan George, which combines his two best-selling books My Heart Soars and My Spirit Soars in one volume. One of his quotes has always stuck with me:

“If you talk to the animals they will talk with you and you will know each other. If you do not talk to them you will not know them and what you do not know, you will fear. What one fears, one destroys.”

With 70% of the world’s animals disappearing in the past 50 years, perhaps we can learn a better way by learning from First Nations peoples.

A Tsleil-Waututh tour company called Takaya Tours offers eco-tours on the Burrard Inlet.

Where To Learn More About First Nations History

If you want to learn more about First Nations on the British Columbia coast and the history of Canada from an indigenous First Nations perspective here are some resources to explore:

1. Visit the Museum of Anthropology (temporarily closed until June 2024 due to seismic upgrades of the Great Hall) at the University of British Columbia, where 7,100 archaeological and ethnographic objects such as artwork and totem poles provide a widespread cultural picture of BC’s First Nations.

2. Book a stay at Skwachays Lodge, Canada’s first Indigenous arts hotel on West Pender Street in downtown Vancouver. They also host a number of First Nations cultural activities.

3. Experience local Coast Salish cuisine by eating at Salmon n’ Bannock, a popular Indigenous-owned restaurant.

4. Download a free Sea To Sky Cultural Journey Guide to learn about the Squamish and Lil’wat First Nations on your next drive to Whistler.

5. Explore Tourism Vancouver’s Indigenous Tourism directory of attractions, tour operators and cultural sites. You should also visit the Totem Poles at Brockton Point in Stanley Park. Here’s a short guide to learn about each of the distinct totem poles.

6. Native Land is a resource to learn more about Indigenous territories, languages, lands, and ways of life.

7. The University of Alberta offers an excellent 12-lesson online course about Indigenous Canada on Coursera.

8. I’m a big fan of watching documentary films to explore interesting topics, so here are 15 excellent documentaries about First Nations and Native American History.

9. Educate yourself about the 94 Calls To Action for Truth and Reconciliation.

I hope you found this post educational and that it sparks your curiosity to learn more about the First Nations peoples living on the British Columbia coast.

- 10 Best Peru Hiking Tours And Multi-Day Treks In The Andes - April 19, 2025

- 10 Best Banff Hiking Tours In The Canadian Rockies - April 19, 2025

- 10 Best Vancouver Hiking Tours In The B.C. Coast Mountains - April 19, 2025